David Wall talked to Radio Sputnik about the problem of Ransomware and the sucesses of the ‘No More Ransomware’ project. Run by a collaboration of cybersecurity organisations (inc EUROPOL) ‘No More Ransomware.org’ offers advice and software to recover computer files encrypted by ransomware and is claimed to have saved over 200,000 victims up to £86 million ($108 million).

Cyber security: Think like the enemy

Lena Connolly and David S. Wall,

The news out this week is that twenty-two US cities have been targeted so far in 2019 and that 170 county, city, or state government systems have been targeted by ransomware attacks since 2013. This is in addition to attacks on many thousands of corporate businesses. In response, 227 city mayors at the 2019 annual US Conference of Mayors pledged that they will not pay a ransom. The crippling crypto-ransomware attacks upon Baltimore, Lake City and Riviera Beach and various large multi-nationals such as Maersk, illustrate the increasing resilience of cybercriminals to maintain ransomware’s position as a major cybersecurity threat. It also illustrates that Cyber-security professionals need to get more cybercrime savvy about crypto-ransomware.

N.B. Links to The Rise of Crypto-Ransomware in a Changing Cybercrime Landscape

Connolly, A. and Wall, D.S. (2019) ‘Cyber security: Think like the enemy’,Computing , 16th July, https://www.computing.co.uk/ctg/opinion/3078977/cyber-security-think-like-the-enemy

The Rise of Crypto-Ransomware in a Changing Cybercrime Landscape: Taxonomising Countermeasures

A new paper under this title has just been published by Lena Connolly and David Wall in the journal Computers and Security.

Here is a summary of Connolly, A, and Wall, D.S. (2019) ‘The Rise of Crypto-Ransomware in a Changing Cybercrime Landscape: Taxonomising Countermeasures, Computers and Security. Available online, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2019.101568

Each year the increasing adaptivity of cybercriminals maintains ransomware’s position as a major cybersecurity threat. Evidence of this shift can be seen in its evolution from ‘scareware’ and ‘locker’ scams through to crypto-ransomware attacks. Whereas ‘scareware’ used to bully victims into paying a fee to remove bad files, ‘lockers’ froze the computer until a ransom payment was made for a release code. Crypto-ransomware, in contrast, encrypts the actual data on the victim’s computer until a ransom payment is made (usually in bitcoin) to release it. In more recent malicious cases there is no release key, it is used as an attack weapon to permanently fry and disable the victims’ data, which can be devastating for the organisation involved and even more disastrous if it delivers national infrastructure.

Using primary and secondary empirical sources, this article draws upon candid in-depth interviews with 26 victims, practitioners and policy makers to explore their reactions to the shift in the ransomware landscape. Our research indicates that a subtle ecosystem of social and technical factors makes crypto-ransomware especially harmful, as a consequence there is no simple remedy, no silver bullet, for such a complex threat like crypto-ransomware. The attackers are increasingly doing their homework on organisations before they attack and hence, are extremely adaptive in both delivering their ever-developing ransomware. They are also tailoring their attack vectors to exploit existing weaknesses within organisations. Successful attacks combine scientific and social methods to employ a variety of ‘social’ techniques to get the malware onto the victims operating system. Techniques that include, for example, psychological trickery, profiling staff, exploiting technical shortcomings, areas of neglect by senior management and a shortage of skilled, dedicated and adaptive front-line managers – basically any opportunity available.

Our findings illustrate the nuanced relationship between technological and social aspects of crypto-ransomware and the organisational setting, indicating that a multi-layered approach is required to protect organisations and make them more resilient to ransomware attacks. Attacks, which are increasingly shifting from simple economic crimes of extortion, to disrupting and even destroying organisations and the services they provide. While the cybersecurity industry has responded to progressively serious ransomware threats with a similar degree of adaptiveness to the offenders, they have tended to focus more upon scientific ‘technical’ factors than the ‘non-technical’, social, aspects of ransomware. So, these observations suggest that organisations need to continually improve their security game more frequently and be as adaptive as the criminals in their responses to attacks. In order to achieve this goal, we developed a taxonomy of crypto-ransomware countermeasures that identifies a range of response tools, which arethe socio-technical measures and controls necessary for organisations to implement in order to respond to crypto-ransomware effectively. We then, identified the enablers of change, the groups of employees, such as front-line managers and senior management, who must implement the response tools to ensure the organisation is prepared for cyber-attacks.

Our research findings, therefore, will not only assist Police Officers working in Cybercrime Units in further understanding the perspective of the victims and also the impacts of crypto-ransomware. But, they have important practical implications for IT and Security managers and their organisations more generally (some of which are police). The taxonomy provides a blueprint for systematising security measures to protect organisations against crypto-ransomware attacks. Managers need to select controls appropriate to their specific organisational settings, for example, the ‘business-use only’ of IT resources is necessary in some organisations, such as commercial organisations, while not practical in others such as research institutions. Also, face-to-face security training, for example, may be more possible and effective in smaller organisations than large ones. The taxonomy also underlines the importance of embedding appropriate ‘social’ based controls in organisational cultures rather than simply focus upon technical measures. This is because, as indicated above, inappropriate measures, skills and support led to incidents occurring, some of which were particularly devastating. Furthermore, the taxonomy underlines the crucial role that mid-level managers play in responding to crypto-ransomware threats.

The skills set for competent front-line management also goes beyond being security and IT-savvy, to becoming organisationally adaptive and to think like ‘the enemy’. Security professionals are not only required to be influential mid-level leaders who can change attitudes and behaviours in organisations by cultivating certain cultural traits. They have to understand both cultural factors and human behaviour and express this understanding in practice to succeed in their role. In return, senior management must be IT-competent and be effective in overseeing the IT functions of their organisation. Senior managers represent an important part of the security chain in organisations and need to support the efforts of mid-managers. Ultimately, both levels have to respect each other’s position to work together co-own the problem to co-produce the solution – something that is easy to say but hard to put into practice. Our future plan is to convert the taxonomy into a more user-friendly tool, similar to the Cyber Essentials self-assessment instrument.

Hackers are making personalised ransomware to target the most profitable and vulnerable

Lena Connolly, University of Leeds and David Wall, University of Leeds

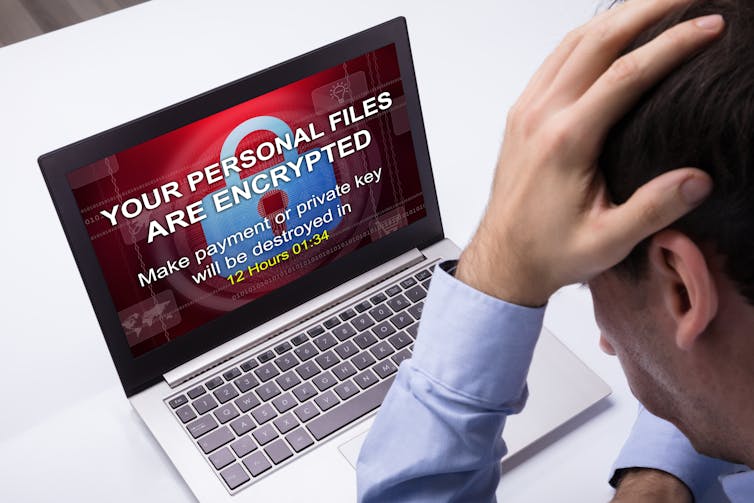

Once a piece of ransomware has got hold of your valuable information, there is very little you can do to get it back other than accede to the attacker’s demands. Ransomware, a type of malware that holds a computer to ransom, has become particularly prevalent in the past few years and virtually unbreakable encryption has made it an even more powerful force.

Ransomware is typically delivered by powerful botnets used to send out millions of malicious emails to randomly targeted victims. These aim to extort relatively small amounts of money (normally £300-£500, but more in recent times) from as many victims as possible. But according to police officers we have interviewed from UK cybercrime units, ransomware attacks are becoming increasingly targeted at high-value victims. These are usually businesses that can afford to pay very large sums of money, up to £1,000,000 to get their data back.

In 2017 and 2018 there was a rise in such targeted ransomware attacks on UK businesses. Attackers increasingly use software to search for vulnerable computers and servers and then use various techniques to penetrate them. Most commonly, perpetrators use brute force attacks (using software to repeatedly try different passwords to find the right one), often on systems that let you operate computers remotely.

If the attackers gain access, they will try to infect other machines on the network and gather essential information about the company’s business operations, IT infrastructure and further potential vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities can include when networks are not effectively segregated into different parts, or are not designed in a way that makes them easy to monitor (network visibility), or have weak administration passwords.

They then upload the ransomware, which encrypts valuable data and sends a ransom note. Using information such as the firm’s size, turnover and profits, the attackers will then estimate the amount the company can afford and tailor their ransom demand accordingly. Payment is typically requested in cryptocurrency and usually between 35 and 100 bitcoins (value at time of publication £100,000–£288,000).

According to the police officers we spoke to, another popular attack method is “spear phishing” or “big game hunting”. This involves researching specific people who handle finances in a company and sending them an email that pretends to be from another employee. The email will fabricate a story that encourages the recipient to open an attachment, normally a Word or Excel document containing malicious code.

These kind of targeted attacks are typically carried out by professional groups solely motivated by profit, though some attacks seek to disrupt businesses or infrastructure. These criminal groups are highly organised and their activities constantly evolve. They are methodical, meticulous and creative in extorting money.

For example, traditional ransomware attacks ask for a fixed amount as part of an initial intimidating message, sometimes accompanied by a countdown clock. But in more targeted attacks, perpetrators typically drop a “proof of life” file onto the victim’s computer to demonstrate that they control the data. They will also send contact and payment details for release of the data, but also open up a tough negotiation process, which is sometimes automated, to extract as much money as possible.

According to the police, the criminals usually prefer to target fully-digitised businesses that rely highly on IT and data. They tend to favour small and medium-sized companies and avoid large corporations that have more advanced security. Big firms are also more likely to attract media attention, which could lead to increased police interest and significant disruptions to the criminal operations.

How to protect yourself

So what can be done to fight back against these attacks? Our work is part of the multi-university research project EMPHASIS, which studies the economic, social and psychological impact of ransomware. (As yet unpublished) data collected by EMPHASIS indicates that weak cybersecurity in the affected organisations is the main reason why cybercriminals have been so successful in extorting money from them.

One way to improve this situation would be to better protect remote computer access. This could be done by disabling the system when it’s not in use, and using stronger passwords and two-step authentication (when a second, specially generated code is needed to login alongside a password). Or alternatively switching to a virtual private network, which connects machines via the internet as if they were in a private network.

When we interviewed cybercrime researcher Bob McArdle from IT security firm Trend Micro, he advised that email filters and anti-virus software containing dedicated ransomware protection are vital. Companies should also regularly backup their data so it doesn’t matter if someone seizes the original. Backups must be tested and stored in locations that are inaccessible to ransomware.

These kind of controls are crucial because ransomware attacks tend to leave very little evidence and so are inherently difficult to investigate. As such, targeted ransomware attacks are not going to stop any time soon, and attackers are only likely to get more sophisticated in their methods. Attackers are highly adaptive so companies will have to respond just as smartly.

Lena Connolly, Research Fellow in Cyber Security., University of Leeds and David Wall, Professor of Criminology, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A new ransomware article published

A new article based on the EMPHASIS work has been published in the Crime Science journal:

Gavin Hull, Henna John, Budi Arief, “Ransomware Deployment Methods and Analysis: Views from a Predictive Model and Human Responses”, Crime Science 8(2), 2019.

The full article can be found at https://rdcu.be/bmtVa

EMPHASIS part of the RISCS research institute

The EMPHASIS project is part of the Research Institute into the Science of Cyber Security, the most interdisciplinary cyber security community in the UK. See the write up by Wendy Grossman of EMPHASIS in RISCS.

Economics of Ransomware at Coventry University

Anna Cartwright is an Associate Professor in Economics at Coventry University and a co-investigator on the EMPHASIS project. Her research interests include game theory, industrial economics and behavioural economics. Recent papers look at the business model behind ransomware and game theoretic models of ransomware. She is a member of the Cyber Security Research Group at the Institute for Future Transport and Cities.

EMPHASIS a partner of NoMoreRansom

The EMPHASIS ransomware project has joined NoMoreRansom as a supporting partner.

If you are a victim of ransomware, do not pay the ransom. Look on the NoMoreRansom site to see if decryption tools are available for this particular ransomware.

Big Data and Machine Learning at Newcastle University

Dr Stephen McGough will be acting as the research lead for the EMPHASIS project at Newcastle University. His research expertise lies in the areas of Big Data, Machine Learning and particularly Deep Learning.

We are also in the process of recruiting a researcher. Please get in touch if interested.

EMPHASIS: EconoMical, PsycHologicAl and Societal ImpactS of Ransomware

This is the website for the EPSRC EMPHASIS “EconoMical, PsycHologicAl and Societal ImpactS of Ransomware” project.

Universities: Kent, Leeds, De Montfort, City, Newcastle, Coventry

Disciplines: Computer Science, Criminology, Psychology, Economics, Law

2017-2019